The brilliantly talented author and illustrator James Mayhew talks to Ian Eagleton about art history, painting to classical music, working with Zeb Soanes and Jackie Morris, resilience and mental health and shares his top tips for developing reading for pleasure…

I was first introduced to your work when I first began teaching through Katie and the Waterlily Pond. Can you tell us a bit more about this series? How did it all come together? Is art history an area that you’ve always had an interest in?

It’s a long story! But in brief, yes – art always fascinated me. I remember looking at famous paintings in a big old book my parents had, and wondering what these “illustrations” were saying, even before I could read. All the usual paintings were there – Mona Lisa, Monet’s Poppy field, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers etc. We lived in the remote Suffolk countryside and had little culture near us – but we did have books. Later, rare trips to London with my sister Katie were like a huge adventure. Visiting museums and galleries planted the seed of an idea – about magical adventures in art. A summer as a pavement artist introduced me to the pleasure of recreating “old masters”, and then at art school – where I studied illustration – all these memories grew into my first book, Katie’s Picture Show, initially as a student project. I never really dreamed I’d get it published, and certainly never expected it to be a series… but it celebrates 30 years in print this year. Many people have queried why I chose a girl heroine, but the reason is quite simple: it’s because the galleries are full of male artists. I wanted to balance that out, using a character based on my sister – the real Katie.

Which period in art history is your favourite and why?

I really love early Renaissance and medieval artists like Giotto and Uccello – they were just starting to explore things like perspective, which gives them a certain charm. They are hugely narrative images, full of storytelling. I especially like mythological themes.

I wondered if you had any feelings about the current education climate – many teachers and schools are reporting that the arts are being pushed out, as the curriculum focus on English and Maths becomes narrower. What do you think about this?

It genuinely troubles me. ALL children need creativity, but there are some who will be genuinely deprived by not having an opportunity to express themselves in a way that is natural to them. There will always be quiet, shy kids who – like me – are not sporty or mathematical etc. The problem, really, is the ignorance that surrounds art – the idea that Art is not a “proper job” or that it is just a picture on the wall. It is so much more – it is the whole structure of civilisation. The clothes we wear, the shoes we walk in, the buildings we live in, cars we drive, TV or cinema we watch, theatre we enjoy – all this involves design and creativity. The record of history and science is preserved in the arts. Art is sculpture, photography, fashion, music, story, poetry, books, literature – it is what sets humans apart from any other living creature. All of this is quite apart from the sheer pleasure it brings. To remove all that is a terrible mistake, and will narrow our influence in the world, lead to more mental health issues and, in my view, starve a whole generation of kids of their right to creative expression. It’s an unfolding tragedy that I fight against with a passion. However it is really important to balance the above by saying that I do see many, many wonderful, inspirational teachers, who do fantastic work in schools, despite the odds being stacked against them (I highly recommend following @MrsPiperKPS on twitter for starters!).

What art lessons do you remember from your own time at primary school?

There were many projects, but in particular a supply teacher introduced me to pen and ink, which frankly changed my life. I’d never used ink before. We went sketching historic buildings in the village, Blundeston, which is where David Copperfield is born in Dickens’s novel. I was ten years old and most classmates struggled with the scratchy old nibs… but I just loved it. Something clicked. I’ve used pen and ink ever since.

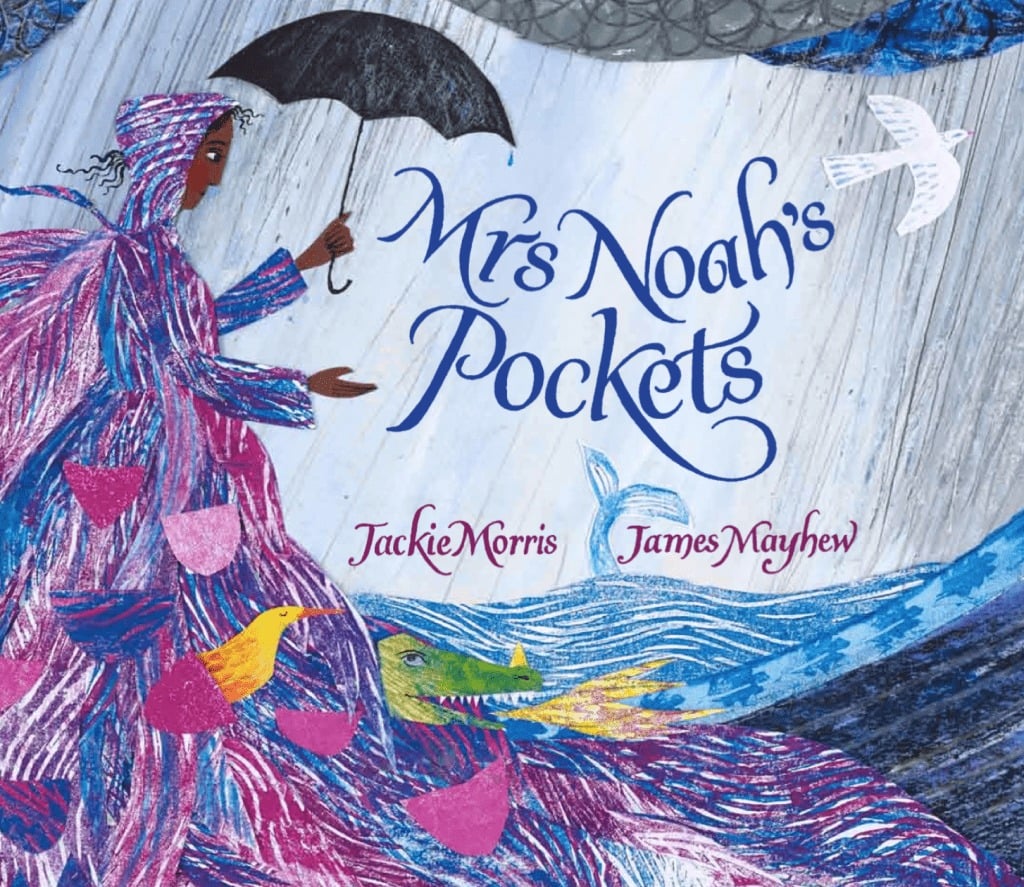

The illustrations and artwork in Mrs Noah’s Pockets is quite different to your other work. What were you trying to achieve in this book?

I wanted to create something bold and strange and magical, with hints of the designs I’d created for Britten’s opera “Noye’s Fludde” in 2013, which were based on Medieval church art. When I saw Jackie Morris’s beautiful text, loosely inspired by the opera, I instinctively felt that the pen and ink work wasn’t a good fit. I had a bit of a crisis to be honest. It was a difficult time, I was terrified of letting Jackie and Janetta Otter-Barry (the publisher) down. But out of this situation, where I just felt completely stuck, came a desire to break away, experiment, rip things up and take a risk. It took a long time – over a year – to dare. Then, with painted paper and a bit of printmaking I started to assemble images and create collage illustrations. My partner Antonio (who, being Spanish, is refreshingly honest) saw this was something very special. It felt brave and new. For this reason I was very happy when Mrs Noah’s Pockets was longlisted for the Kate Greenaway Medal – my first ever nomination.

What was it like working with the brilliant Jackie Morris? Can you describe your professional relationship and how you worked whilst creating Mrs Noah’s Pocket?

Jackie and I go back many years, and I’ve written for her in the past. It was always an unspoken deal that one day, she would write for me. I think it’s a wonderful text, and of course Jackie completely understands how to write in a way that leaves space between the words for an illustrator to be able to imagine. Our working relationship is very much based on trust and respect. She’s a great friend and ally, and I know I can be allowed to be myself. Which was very important at that time of experiment, I think. She supported every step of this big adventure with wholehearted encouragement. It’s quite rare to find someone like that to collaborate with. I’m very lucky.

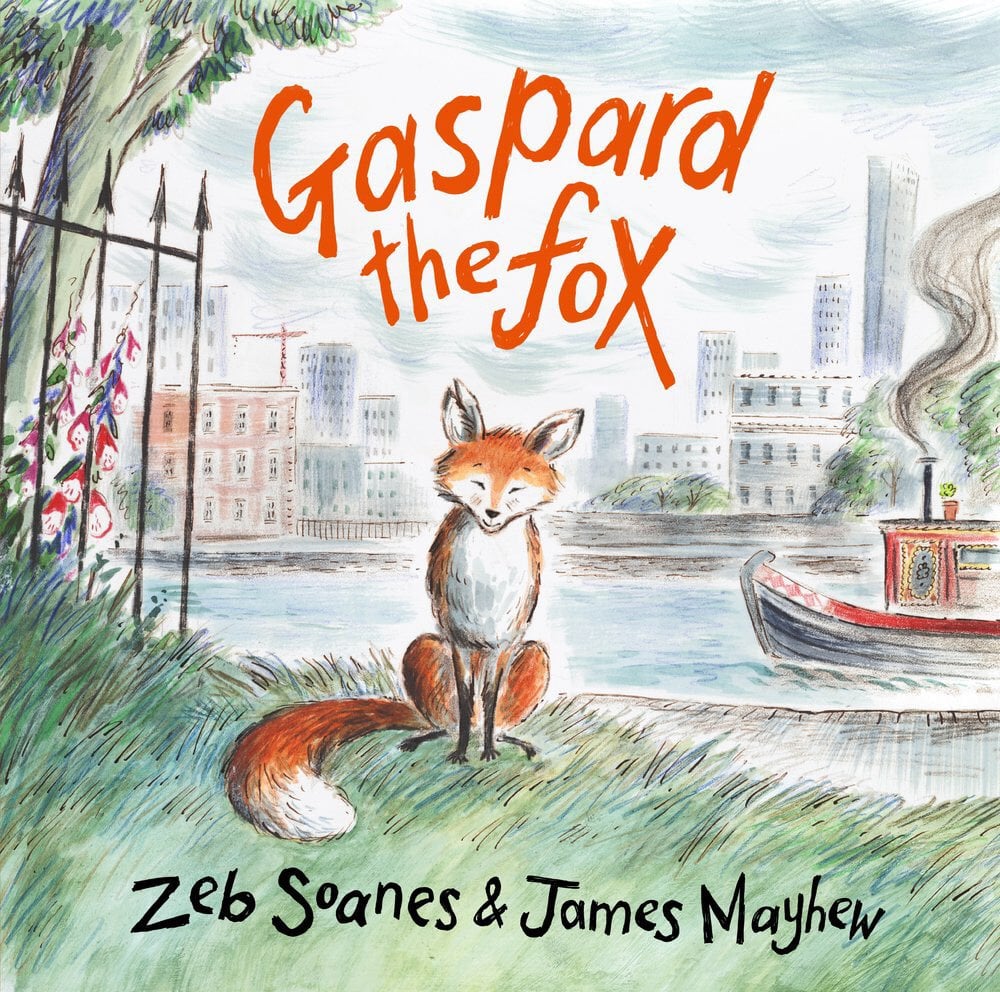

You’ve recently worked with Zeb Soanes on Gaspard the Fox. How was illustrating this book similar to your experiences illustrating other books? How was it different?

This was a very different experience for many reasons. It was the first time I’ve illustrated a book so deeply rooted in the real world. I suppose Katie in London is the nearest to that, many years ago. But this was about a real fox in a real place in North London. I found it rather satisfying to start with reportage sketching and developing illustrations from those studies. I was also very sensitive to the underlying messages of kindness and acceptance, which matter to me. In terms of illustrating technique, I felt it needed something fresher and more painterly than my earlier work. The Mrs Noah collage wasn’t right, but some kind of pen and ink, and some pencil for softness – it took a bit of experimenting to find the right feel.

Traditionally authors and illustrators rarely met or collaborated closely. I’ve been exceptionally lucky – working on Gaspard was a joy and Zeb has become a great friend. We’ve had so much fun presenting Gaspard at festivals and events. We work together uncommonly well. He’s very funny, and he’s the most generous and warm colleague imaginable.

I was particularly interested in this illustration from Gaspard the Fox – the colour palette is limited but it’s very striking. What were you trying to achieve here? Did you spend a lot of time observing the animals you were drawing?

I did meet the real “Finty” and the real Gaspard – who was particularly mercurial and hard to sketch. But I made a few wobbly sketchbook notes, and made many mental observations (how joints bend, length of tail, how ears move…), which are not just useful but essential when creating the characters. I then drew them over and over, many hundreds of times, until they felt properly “warmed up” and started to come alive on the paper. I wanted to keep the palette limited, mainly for a personal aesthetic reason. But also because I think the narrative is often enhanced by a careful use of colour. Here, the red balloon has been accidentally lost; the dog is scared (in her red collar); the flecks of red in Gaspard’s disguised sooty coat are heightened. All three are elements of danger. You’d lose that cohesion and symbolism if you had too much colour.

I’m interested in the relationship between your writing and your illustrating. Does the writing come first or the illustrations? How does one affect the other? Do you have a preference for one form over another or are the two inextricably linked for you?

Every book is different and unique, and there is no formula. Usually some words come first. But Ella Bella Ballerina began with drawings of a theatre… before I wrote a single word. So it can go either way. I can’t just write a story and then draw pictures. It doesn’t really work like that, unless I write for another illustrator, and let the text go off to live in someone else’s imagination. With my own books, as soon as I start illustrating, I change most of the words anyway. That’s the best approach – to keep both image and text fluid so they can be dovetailed. I think I’m getting better at that as time goes on – it’s something you only learn by being deeply immersed in the world of books, the rules and limits… and the audience! I look back at some of my older books and wish I could rewrite them with the benefit of hindsight!

Both Jackie and Zeb have been unusually understanding of this process, and have allowed adjustments to their texts as the images have evolved, which is unusual, but very much to the benefit of the books.

Has technology changed the way you illustrate your work? If so, how?

No, I don’t really use digital technology. Publishers often expect it – and sometimes I’ll scan the art and send it in digital form, for their own ease. I can use photoshop well enough, and clean up the scans as needs be. I might use it to mock things up, or add text to a poster for an event. But I don’t create any art digitally. All the artwork is real. I like to get my hands dirty and feel and smell the paper and the tools I’m using. That brings me a lot of pleasure. For me, it’s a physical process.

What challenges did you face when you first started? How did you stay resilient?

It was simpler world, but in many ways much harder when I started out, in the 80s. Picture books were not taken at all seriously, and illustration was rather sneered at. No-one believed I’d ever actually make a living. Nowadays, illustration is far more respected and there are more colleges, courses and opportunities. The internet is a huge advance with promotion, learning and communication.

But beyond that, I think there were two main challenges. From publishers it was the expectation to have a strong “style” which I never had and never wanted to fabricate. Publishers like to make authors and illustrators into a “brand”, but I always resisted that, probably to the detriment of my career but very much to the advantage of being able to grow, evolve, learn, develop and experiment.

The other challenge – and many illustrators will recognise this – is the challenge from within, my own demons, the solitude, the mental health implications of that, the fear of failure.

I once had two years of counselling and the irony was pointed out that in publishing, the key phrases are “Acceptance” and “Rejection”. I sometimes did question my choice of career!

As for being resilient I’ve had highs and lows, I won’t pretend it’s been easy, but I know there is nothing else I ever wanted to do, so I’ve somehow always dusted myself down and continued. It really is that simple.

What advice would you give to teachers about how to develop reading for pleasure in their classrooms and schools?

Three things:

- Illustration! Allow children to love, look and linger over the pictures. Don’t rush them to the words, and don’t ever imply words are superior. I only learned to read because I loved the illustrations in books so much. So fill the school with art and illustrations and narrative images, and have picture books and comics all the way to Y6.

- Read to your children. The last 20 minutes every day, read a chapter, or a few pages. Show them that YOU relish stories. Make it special, make it yours. Read the books YOU love.

- Have a library in your school! Fight for it, find a place for it. The symbolic value of a library cannot be overestimated. It shows everyone that books are something special. And use that library. Have a regular lending culture, so children see all kinds of books.

What advice would you give to any budding young illustrators?

Keep sketchbooks, observe, look. Don’t try to contrive a style or produce generic stuff that anyone can do. Be unique and be real. And don’t assume a computer will make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. It won’t. Work hard, be pleasant to clients, and always remember the child you are creating your books for – find that child-like innocence inside yourself and call upon it. Work on subjects that excite you, share your passions, speak from the heart. Don’t sell out, be authentic and have integrity. BUT don’t sell yourself short either. Believe in yourself, demand good, fair terms, get a proper credit, and a rock solid contract and appropriate rights. Don’t be bullied by publishers. Join the AOI or Society of Authors.

Finally, can you tell us a bit about what you’re working on next and what we can expect from you in the future?

There will be more from Gaspard and Mrs Noah. I’m also excited about the revival of Mouse and Mole (stories by Joyce Dunbar). But the work I do with musicians and orchestras, painting live illustrations in performances, has expanded hugely, so there will be many more events and this has also inspired my next book: Once Upon a Tune – a collection of some of the myths and stories I’ve discovered hidden away in classical music. I’m hugely excited about it. It will be published by Otter-Barry Books in 2020.

2 responses

Great interview James. I am very interested and excited about your upcoming project. I hope your ‘Once Upon a Tune’ books are a success. It truly enhances the music if you know the story behind it. I’m sure this could well be a ‘recommended read’ for school children as a link between the music, story telling and art. I look forward to seeing for myself.

Really the most fascinating interview about illustration that I have read.