What a treat to welcome author P.J. Canning into The Reading Realm today to tell us all about some amazing scientists and the power of story-telling in science!

What’s 21% MONSTER all about?

Fun, fast-paced, high-octane action adventure, 21% Monster is a perfect page-turning new series for fans of Alex Rider, Percy Jackson and the MCU generation.

When Darren Devlin is arrested for destroying his school with his bare hands, it’s not just the police who are after him. Enter Marek Masters, 14 years old, 19% alien, and the most intelligent, most wanted “almost human” alive. Marek is here to tell Darren the truth – he is 21% monster, and together they must take down the secret organisation that created them.

Darren and Marek are wanted, powerful and dangerous. And now it’s payback time.

‘Three scientists I think you should know about‘ by P.J. Canning

As a chemist myself, I was excited to be asked to write about three scientists, but my mind didn’t take me where I expected. Rather than necessarily picking out my favourites, I found myself thinking about the stories of three who helped me understand the way society, individuals and beliefs shape science and vice versa. I hope you find their stories interesting.

Beatrix Potter

I’m sure you know that Beatrix Potter wrote some very successful and brilliantly illustrated children’s books. So, perhaps its no surprise that, as a scientist and a children’s writer myself, her own story appeals to me. However, it is also a story that makes me rather sad.

Looking at what we know of the young Beatrix, she seems very much a potential scientist. She was shy, thoughtful and liked to invent secret codes only she could understand, but more than anything she loved to draw. She became exceptionally good at scientific drawings of animals, plants and fungi. Amazingly, through studying fungi, she identified that sometimes two different organisms live together in a way that makes them rely on each other to survive. This is called symbiosis.

Beatrix Potter tried a number of times to present her work to scientists, but she was thwarted. In the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century (she was born in 1866), woman doing science was frowned upon. It was considered a man’s work. Many scientists refused to speak to her at all. Only once did she manage to have her ideas presented to a group of scientists, but even then she had to ask her uncle to present it for her. Her work, even then, was ignored and eventually she gave up.

Yes, Potter went on to write some exceptional children’s books, but she was robbed of the opportunity to choose science instead of, or as well as, writing fiction.

Women still face some prejudice in science, but the situation is much improved. It is interesting to wonder how scientifically advanced we’d now be if women had been allowed to study science for the whole of the last two hundred years. Maybe global warming would have already been solved. We’ll never know.

So, from Beatrix Potter’s story I learnt two things:

- Everyone should have an equal chance to do science,

and

- You don’t have to choose between creative pursuits and scientific ones. If Beatrix Potter did both, so can you.

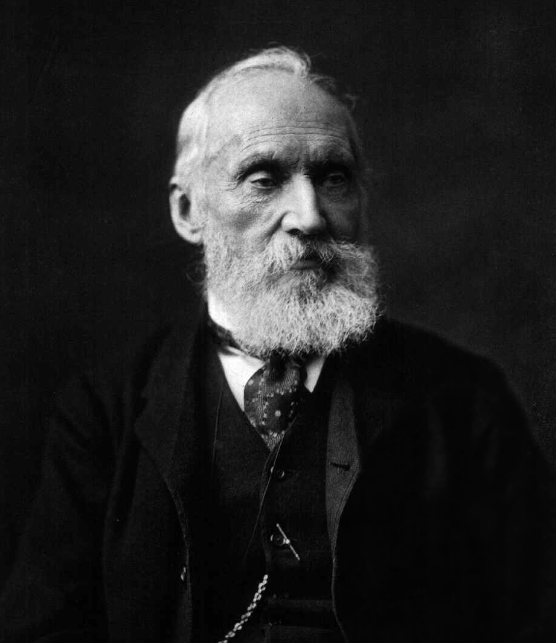

Lord Kelvin (or rather, his Darwinian mistake)

Lord Kelvin was one of the greatest scientists of the nineteenth century. His achievements would take a long time to list and even longer to explain. He was one of the people who invented modern Physics and his ideas and mathematical equations on heat and energy underpin a lot of physics and chemistry even today. However, it was an error he made that really makes him stick in my mind.

Lord Kelvin worked at the same time as Charles Darwin and he really didn’t like Darwin’s ideas. People often say that Darwin invented the idea of evolution. The reality is more subtle. Others had been considering the idea, but earlier versions assumed that God was directing the process. Darwin disagreed. He showed that, if it had hundreds of millions of years to happen, evolution could happen by natural selection. The members of a species best suited to the current environment would survive and others wouldn’t and so over a long time the species would change, or evolve.

Darwin was later proved right, but at the time many people hated the idea because it meant the idea of God wasn’t needed to explain life. In late nineteenth century Britain, this was scary and offensive. So many people, including Lord Kelvin sought to prove Darwin wrong.

What Lord Kelvin did was work out how old the Sun was. He knew its size and how much heat it produced. So, he could work out how long it could have been radiating heat. He was pleased to discover that the Sun could only be twenty million years old. Darwin’s ideas needed life to have been around for hundreds of millions of years. But without the sun, Lord Kelvin argued, there is no life. So, you have to have God to speed up evolution.

Darwin died without knowing if his theory would survive Kelvin’s ideas. Decades later, nuclear fusion was discovered. This is a far more efficient way of creating energy than anything Lord Kelvin had known about. We now know that the Earth and the Sun are billions of years old.

Kelvin’s mistake is called ‘confirmation bias’. He only cared about evidence that fitted what he wanted to be true. There was other evidence, from rocks, that said the earth and life was older. Lord Kelvin didn’t want to know. If he had not wanted to be right, his work would have been interesting anyway. It showed there was an unknown energy source in the Sun, but instead he used it to discredit one of the greatest theories in the history of science.

So, I learn one thing from Lord Kelvin (and the many excellent scientists who have made the same kind of mistake, including Albert Einstein):

- Don’t let what you want or believe to be true stop you from seeing what is actually true.

Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale is my final scientist, although she probably would have considered herself to be no such thing. Also born in the nineteenth century into a wealthy household, she defied her parents to become a nurse. She was quite brilliant at this. During the Crimean War, she hugely improved the care of injured soldiers, saving many lives, and became widely known as the Lady of the Lamp.

However, it is what she did afterwards that was her most influential work. She hired brilliant statisticians to use maths to work out the best way to improve care of patients. The findings were startling, for example showing how important hygiene was, but there was a problem. Most people couldn’t understand the data. All they could see were lots and lots of numbers. Florence Nightingale, however, had the answer. She invented ways of showing the information as graphs and diagrams. Suddenly, lots of people understood and so changes were made in hospitals. These days, we still use the same kinds of pictures to explain scientific data. You expect to see statistics as a graph or pie chart. That’s because of Florence Nightingale.

So, I learnt one thing from Florence Nightingale:

- It’s not just what you know. To make a difference, you have to be able to explain it in the simplest possible way.

The power of stories in science

Something, I imagine, that many people don’t know is how many stories scientists tell other scientists. During my undergraduate degree I was forever being told anecdotes about errors and breakthroughs certain people made and often how a person’s perspective, social standing or beliefs influenced whether they were right or believed. The stories about errors were often the most detailed – cautionary tales about going beyond evidence, refusing to believe what is in front of your eyes, or a scientist’s ideas being shouted down for no good reason.

Far from being a calm and logical pursuit, science is practiced by flawed, emotional humans. So, these stories are as vital to learning how to be a good scientist as being taught how to write a good hypothesis. Perhaps, then, it is no surprise that I’m not the first and certainly will not be the last scientist to also write fiction. Storytelling binds the two pursuits together.