Kate Wakeling’s first collection of poems for children, Moon Juice (illustrated by Elīna Brasliņa) is published by The Emma Press, and won the 2017 CLiPPA Prize and was nominated for the 2018 Carnegie Medal. Here she talks about her writing process, the beauty of poetry, ethnomusicology and also gives some top tips about how to explore poetry in the classroom…

Without giving too much away, can you give us a bit more information about Moon Juice?

Moon Juice is a collection of all sorts of different poems: there are stories, characters, lists, spells, riddles. I wanted the book to feel a bit like a rainbow, touching on all sorts of different colours, moods and atmospheres. The poems are often pretty mischievous – the book has some unlikely characters like Hamster Man, Rita the Pirate and Skig the Warrior – but I wanted to explore serious things too, so the book also touches on themes like death, difficult emotions and the nature of authority. I am keen always to try and talk about important things in an unsentimental way and with a good peppering of humour. And I love – and I mean really really love, possibly more than any other activity I can think of – fiddling about with words – finding unexpected rhymes and chimes between different words. One of the biggest aims I had in the back of my mind when writing Moon Juice was to try and encourage younger readers to discover the joy of playing around with words for themselves.

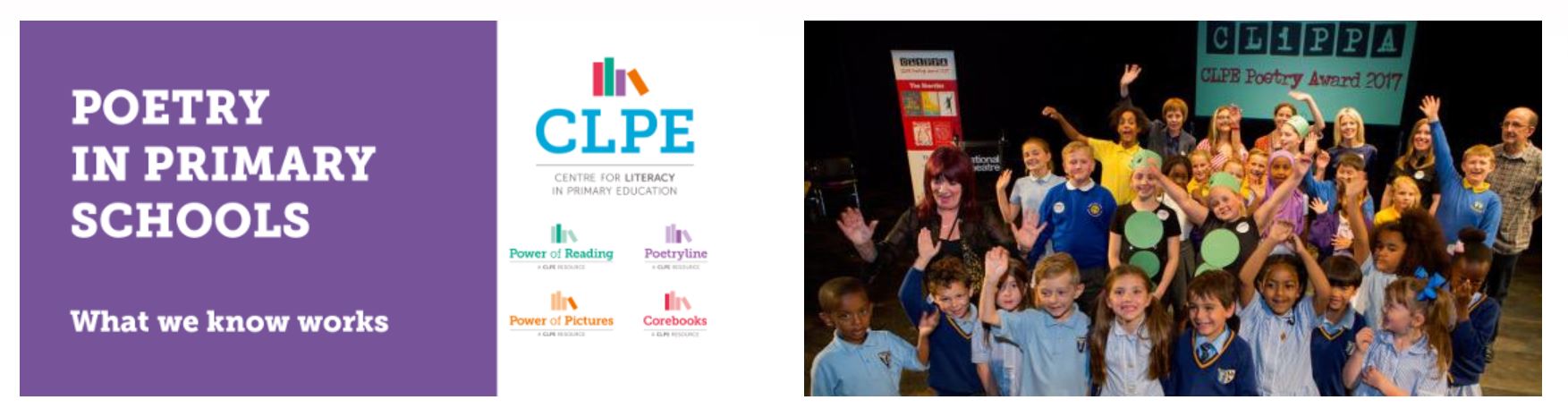

Moon Juice won the CLiPPA 2017 award. Do you remember where you were when you heard the news? How did you feel?

I was actually at the CLPE’s wonderful Poetry Show at the Olivier in the National Theatre with all the other shortlisted poets and what seemed like a zillion brilliant school children in the audience. When the judges announced my name as the winner it was a completely overwhelming sensation – of equal parts joy, surprise, gratitude and terror. A heady cocktail that I countered by eating a frantic quantity of cakes at the reception afterwards while standing awkwardly by the stairs.

What would you say the main themes in Moon Juice are?

Gosh, all sorts. Animals, space exploration, the importance of the imagination, being overwhelmed by difficult emotions, Indonesian myths, the trickiness of authority, the power and value of children’s perceptions, how important it is to try and really take-in the world around us, the joy of words as sort of ‘sound objects’ in their own right.

Do you have a favourite poem in Moon Juice?

I think my favourite poem in Moon Juice is ‘The Demon Mouth’. It’s about an enormous and fearsome mouth that devours everything it finds, until someone takes the time to actually feed it. The poem explores ideas of compulsion and the need for tenderness, but the story is also told through some rascally wordplay. I love that the poem seems to have resonated with both children and adults alike, and I also particularly love Elina’s illustration of the kind ‘medicine woman’ who saves the day in the poem.

I really loved the poem My Ghost Sister – it’s very moving and poignant. Can you tell us a little more about this poem, the inspiration behind it and what you were trying to achieve?

Oh thank you! That’s wonderful to hear. I wrote the first batch of poems for Moon Juice while I was pregnant, and My Ghost Sister was sparked while I was on my way to have the 5-month scan of this baby. I started thinking about how I might feel if something were to go wrong – how I had such a strong sense of this tiny spirit inside me, even though I’d not yet met him. I had an urge to write a poem about grief and about the mystery links that can exist between people, and as I thought about how I might write such a poem that felt suitable for children, I had the idea of exploring that deep connection often felt between siblings and what the loss of a child in a family might be like – and the poem flowed from there.

I also enjoyed The Ten Dark Toes at the Bottom of the Bed – it wonderfully captures the irrational fear of childhood and night time! What were you scared of as a child?

My top-priority fears were, as I recall: darkness, falling down the crack of an earthquake, gremlins, quicksand and the possibility of nuclear poisoning after an atomic bomb. Not all these fears have gone away, but I at least feel pretty relaxed about quicksand these days.

In the poem Night Journey, you describe a car as a ‘thought machine’ and talk about new thoughts sizzling out into the dark. How important do you think daydreaming is for children?

Hugely important! Time to look out of the window is at once the greatest luxury and the greatest necessity. And not just for children: space to think and imagine is so vital for adults too. I don’t drive a car which is often something of an administrative disaster for me, but it does mean I get to look idly out of the window of vehicles quite a lot, which is where I reckon at least half my poems begin.

There are many different types of poems in Moon Juice with a variety of structures. How do you decide on the structure, layout and form of a poem? Do you have a favourite type of poem to write?

Sometimes I have in mind the form of a poem before I start. A poem like ‘Little-Known Facts’ which is a list of outlandish facts ‘known’ only to children (e.g. ‘In secret, children can turn lightbulbs on and off with just their eyebrows’) was a list poem from the off, while ‘Comet’ – a poem that attempts to enact the ferocious pace of a comet rushing through space – felt like it had to be tightly-rhymed couplets. But other poems sort of fall into place in terms of their form through the writing. I’m not sure what my favourite sort of poem is to write – I do have a soft spot for a prose poem that looks quite un-poem-like on the page but which zings with rhymes and alliteration in the reading. My poem ‘Hair Piece’ is one of these and it still gives me weird burst of pleasure to read it out (even if the poem is something of a humiliating confessional about getting a really bad perm).

What exactly is poetry? Can it be defined?

Ha, yes, poetry isn’t an easy thing to define, but I guess (for me) poetry is language that is fully alive to its own music.

What was it like seeing your poems illustrated by Elina Braslina? What do you feel the illustrations add to the collection?

Ahhhh, I absolutely love Elina’s illustrations. Elina had such a complete and intuitive understanding of what I was hoping the poems might say, and her illustrations brought each poem alive in a wonderfully new, insightful and witty way.

Which writers, poets and authors have inspired you would you say?

I was a pretty obsessive reader as a child but didn’t read very much poetry, funnily enough. I was an enormous fan of Roald Dahl and was also quite fixated on reading (and re-reading over and over and over again) some lovely but perhaps rather old-fashioned books like L.M. Montgomery’s ‘Anne of Green Gables’ series, Laura Ingalls Wilder’s ‘Little House’ books and everything by Frances Hodgson Burnett. I suppose the characters in these books tend to be adventurous, upstanding and adept with words: three things I definitely aspired to be when I was small. (And continue to aspire to be now…)

As well as being a poet, you are an ethnomusicologist and studied music at Cambridge University. Can you tell us a little bit more about what an ethnomusicologist does? How would you say this has influenced your writing?

Ethnomusicology is all about exploring music in its social context, so thinking about why and how a certain group of people might make a certain sort of music at a particular time and in a particular place. I suppose it’s a little like finding the story behind the music-making. After studying straightforwardly classical music at Cambridge I went to the School of Oriental and African Studies in London and did a PhD in Balinese music, which involved a year’s fieldwork in Indonesia getting really involved in the everyday life and music of Bali. I think my experiences in Indonesia, particularly getting to know lots of Indonesian people both in Bali and in the UK brilliantly disrupted my (at that time I’m sure pretty narrow) understanding of the world in all sorts of ways. It made me open up to different ways of going about things, which I think is what poetry is up to as well. And I guess ethnomusicology helped me really love music again. I was a bit fed up with some aspects of classical music after my first degree, but getting deeply involved in Balinese music (and dance) felt tremendously uplifting and exciting. It shook me awake! In turn, I think music is a massive influence on my writing – I love being really, really picky about all the ‘sonics’ in the words I use, and am also pretty obsessed about the rhythm of text, be it when writing couplets or completely free verse – rhythm is central to absolutely every kind of poem.

How is music similar to poetry? How is it different?

Language can of course signify in a way that music (mostly) cannot. But I’d say of all the forms of writing, poetry is the closest of all to the great mystery of music, in that it comes alive inside an individual’s ear and that it can tap into our emotions in so many rich and unfathomable ways.

Some of your poems were inspired by Indonesian culture. Were you surprised by the ‘Reflecting Realities’ report carried out last year by CLPE, which found that only 4% of children’s books published in 2017 featured BAME characters? What can publishers and writers do to address this?

I wasn’t that surprised by this figure, sadly. It’s an appalling statistic and it reflects a serious inequality of opportunity and representation across every quarter of the publishing world. The issue needs to be addressed by championing people of colour to work throughout the publishing world, so that means authors, illustrators, editors, commissioners, marketing staff, absolutely everyone who works in children’s books – and it is also incumbent on white writers to look at who is ‘populating’ their books and to open their eyes and brains and make sure that BAME characters are fully realised and not just ‘ciphers’. This happens too and it’s absolutely not OK.

What do you think poems can offer children that other stories or forms of writing can’t?

For me, poetry is the complete package. It takes us to other worlds. It lets us into other minds. It fuels the imagination and invites us to play. It asks us to celebrate language for its beauty and strangeness. It helps us express ourselves. And perhaps most importantly, poetry calls on us to value the space between the black and the white of things: poems tend to whisper not shout, and a good poem offers some space for the reader to find their own meaning. All of these things feel to me like crucial elements in both learning and living.

When I taught, I was always a bit worried about teaching poetry and I know many teachers find this a difficult area to teach. Why do you think this might be?

I think lots of adults had not-brilliant experiences of poetry at school themselves – perhaps being instructed to conduct a sort of autopsy on an often rather staid choice of poem. And I think poems can seem a bit worrying because they are so unstable. If you are looking to pin down the ‘meaning’ of a poem in a concrete way, you often tend to be disappointed as poems are slippery things and they tend to slither out of reach just as you think you have a handle on them. This can make poems a bit daunting to bring into a classroom, but sharing and discussing a poem with a group of children can also be hugely liberating and exciting.

What advice would you give to teachers about how to approach the teaching of poetry?

I think being open to lots of different interpretations is central to exploring a poem in a group. And being alive to poems as things to be sounded out is important too. Performing poems (both children’s own and existing poems) is a brilliant way of engaging children in the beauty, drama and mischief of poetry. Crucially, performance allows all the nuance and craft of poetic language to sound and so to be received by children in an enjoyably effortless way – we can enjoy the deep pleasure of a half-rhyme or a tight rhythm without the effort of engaging with the written word which can sometimes be a challenge for children. CLPE’s Poetryline is a wonderful resource, full of poets performing their poems and talking about their work in lively, accessible ways and is an excellent way to help encourage children to engage with poetry.

What advice would you give to any young budding poets?

Firstly, go for it. A poem can be whatever you want it to be: long, short, sad, funny, something in-between (as many of the best ones are). I’d say when you begin a poem, first be as wild and messy and free as you can – write as though your pen or keyboard is on fire! – then change hats and become as patient and picky as possible.

For me, writing a poem is half about letting your imagination zoom and half about being furiously fussy to make sure every word counts. Lastly, try not to choose words just for what they mean but explore how they sound too. If you let these sounds lead the way, all sorts of unexpected and excellent things will happen to your poem.

Can you tell us what you’re currently working on?

I’m finishing a second collection of poetry for children (which so far features toucans, peas, dinosaurs, ghouls, frost, clouds, moths and a really weird cake) and I’m also writing some poems for adults too.

Finally, can you describe Moon Juice in three words?

Serious word-mischief.