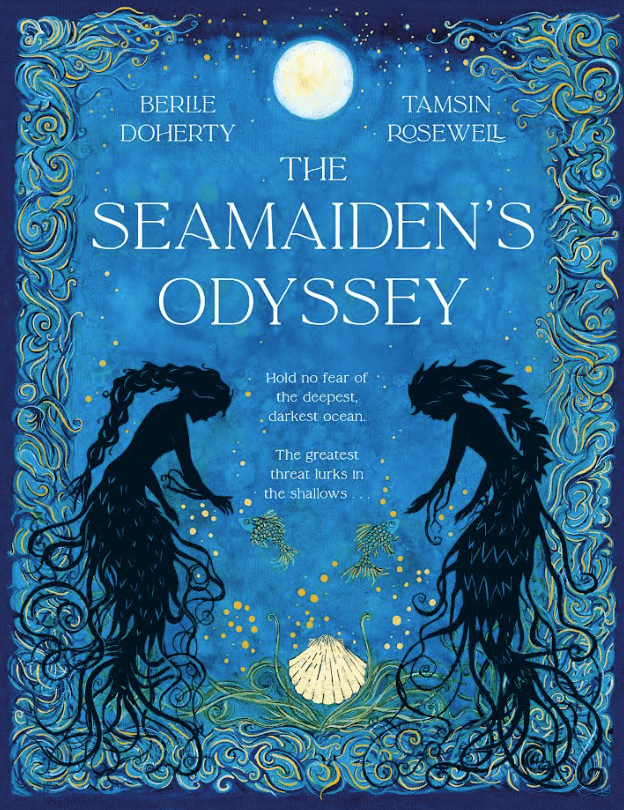

What a treat to welcome Berlie Doherty and Tamsin Rosewell into The Reading Realm to talk to Ian Eagleton about their beautiful, mysterious and lyrical new book THE SEAMAIDEN’S ODYSSEY!

Before we settle down in The Reading Realm and chat about your new book, what’s your drink and snack of choice?

Berlie: I think I’ll have a really well-made coffee, and maybe a slice of GF flapjack.

Tamsin: Something cosy and autumnal; my dearest wish is to live in Brambly Hedge and spend my days making blackberry jam and apple cake. So I’m going for homemade jam tarts with a mug of rosehip tea, please.

What does The Seamaiden’s Odyssey mean to you?

Berlie: For me, place is one of the most important characters in a story. I wanted to explore somewhere different and new. It’s a story about a journey from the safe and beautiful haven of home to somewhere unfamiliar, alien and frightening. The call of home is so strong that Merryn finds a way, the only way, to return there. It was a challenging journey for Merryn to make, but also a challenging creative journey for me. I love the sea, and grew up in a small coastal town, but the oceans are vast and complex, and the idea of a society of sea-dwellers, with all their familial ties and conflicts, gave me a chance to explore something totally new.

Tamsin: For me this book was an amazing opportunity to collaborate with a truly great writer and explore our shared interest in folklore – in both storytelling and imagery. When we started the project, Berlie would send me her draft chapters and ideas about how her story was going to develop, and I would respond visually. We had long conversations about what we wanted our seamaidens to look like, for example. We wanted to step away from the very loaded, ultra-feminine image of a mermaid with a pink sparkly tail and a pretty clam-bra! But we did want them to look beautiful in their own way, and very ‘other’. That otherness is incredibly important in the folklore of mythological sea creatures, and part of its importance, I think. They’ve long been a way for humans to explore what happens to humanity when an individual becomes an outsider – when they don’t look and feel like others, when they make decisions or have attributes that set them apart from their community.

What would you say the main themes in The Seamaiden’s Odyssey are?

Berlie: Certainly the powerful ties of family, and particularly the relationship between generations. Merryn has a very strong relationship with her grandmother Kessa and her sister Jania in particular. I often write about the search for identity, and I think this is a major theme here. As soon as Merryn rejects her father’s wishes for her, she realises she is alone and afraid. She faces curiosity and exclusion because she enters into a society that is not her own. But there are other aspects of the initial reponse of the villagers she encounters; hatred, or love that is so strong that it becomes possession. Merryn has to learn about herself, but also about how she is perceived by other people.

It’s also about love. When Merryn meets Howie she must make a heart-rending choice. In the same way, in the framework story, Sasha the marine biologist has to make an unbearable sacrifice by letting her go.

Also it’s about the power of nature, understanding and exploring our planet and fellow-creatures.

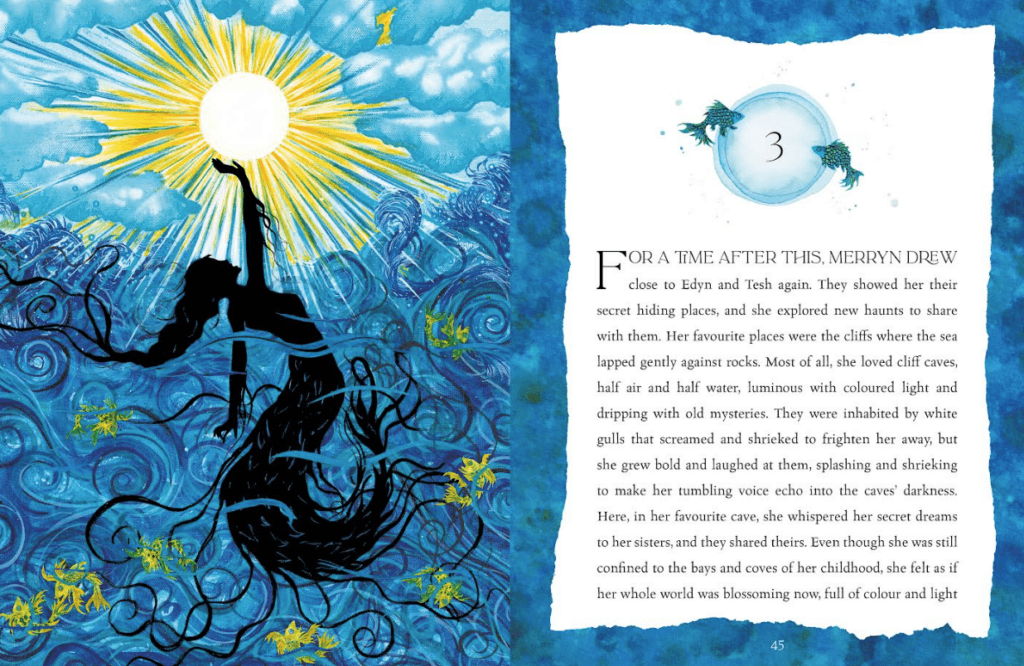

Tamsin: Visually, I’ve really focused on how the characters connect to each other as a family: I wanted to visually represent the different generations, the conflicts and fights, the moments of danger, and of reaching for independence. For example, in that opening double page spread, we can see Jania separated from her family – and I’ve used the ‘gutter’ (the place in the book where the pages fold) to really divide her. She’s in danger and her family is reaching out for her, but huddled in a group the other side of that divide. Also, on that theme of independence, there’s a double-page spread of Merryn alone and, for the first time, exploring outside her known world. She’s alone and in a cave that is very different from her bright, ocean-blue world. Being independent is exciting, but it can also be frightening. I needed her aloneness to be the focus of that image.

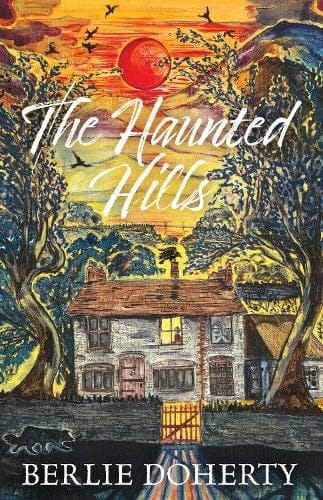

I know you both worked together on The Haunted Hills. I wondered how The Seamaiden’s Odyssey was similar and different to this?

Berlie: The experience was very different. I wrote The Haunted Hills during the pandemic. Writing is always an isolating experience; even when you’re with people, the story you’re writing is in your waking and sleeping thoughts. In the usual way, I submitted my story for publication and the publishers UClan, sent me some portfolio artwork of three different illustrators to consider for the cover. The Haunted Hills was for young adults, so I sent the artworks to my grandchildren to see which illustrator’s work appealed to them most. Like me, they all chose Tamsin’s work because of her vibrant use of colour. Tamsin then worked on the cover alone – and we didn’t actually meet until the book was launched! That in itself was a lovely, and unusual experience, as Tamsin brought her artwork for the cover and explained to the guests and to me how she had worked on the cover idea.

After that, Tamsin worked on covers for two of my earlier books which UClan were republishing, Children of Winter and Granny was a Buffer Girl.

And I loved her work! We decided we would like to work together on a picture book, and it was Hazel Holmes’ idea that it could be a fully illustrated novel for a YA readership. We were very excited by this proposal, and also quite nervous. It was an ambitious project, and we were set to work together from the very start, rather than for me to write the story and then send it to Tamsin. We had many conversations (thanks to Zoom!) about folk stories, legends, colour, styles. We never disagreed, but inspired each other and were mutually delighted by the results as words and images flowed!

Tamsin: The Haunted Hills was the first book I illustrated for Berlie. By the time I was brought on board the book was written and complete, and ready for typesetting. With The Seamaiden’s Odyssey I was involved from the very start. I remember our first discussion about inland mermaid folklore, what of it remains and what is now lost – and how it might connect to the characters like Jenny Greenteeth who are water-dwelling spirits but not really ‘mermaids’. I think that way of working is really quite unusual in the book industry today. It is more normal for an illustrator to be chosen by the publisher, brought in at a later stage and often only given a fragment of text and the publisher’s description to work from. What the books have in common is their focus on our landscape and folklore – which Berlie writes incredibly well! They both have links to that amazing, dramatic Peak District landscape too.

Do you have a favourite illustration? (include images of both please and explain why it’s your favourite!)

Berlie: Oh gosh, where do I start! I would choose a different one every day! But today, I choose the illustration for the text which is on page 43. Merryn has finally been given permission by her grandmother to swim alone, and in daylight, to the dangerous surface of the ocean. In Tamsin’s illustration, Merryn emerges with her hand outstretched towards the glorious light if the sun. It is almost as if she’s holding all the power of the sun in her hand. It’s such a symbol of hope, beauty and fulfillment, and I take this triumphant image with me to the very conclusion of Merryn’s story.

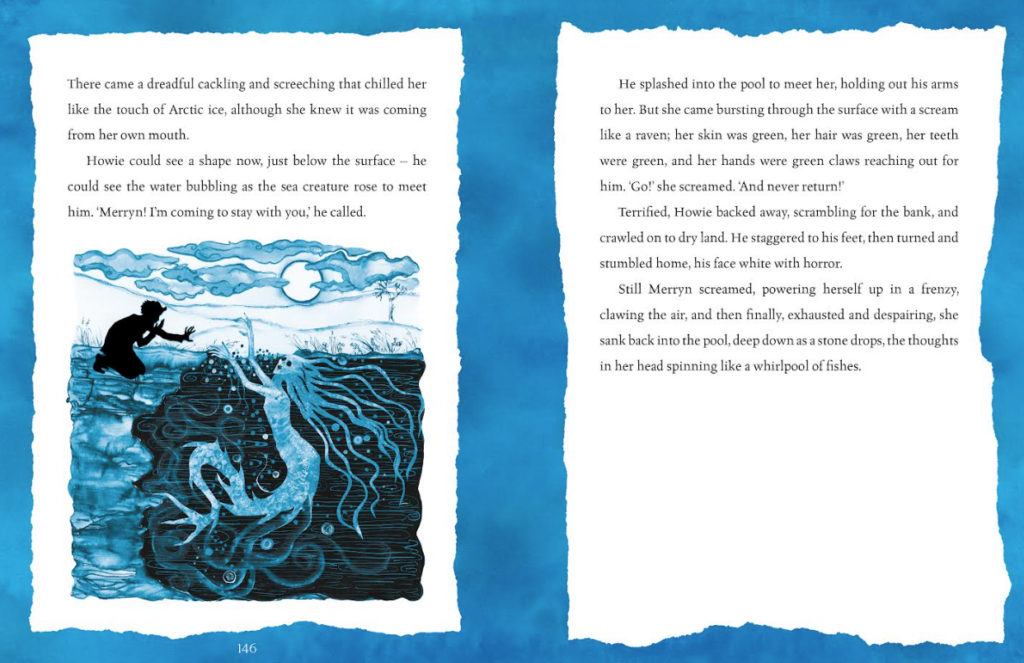

Tamsin: I love working in colour most of all, but one of my favourite images is one of the black and white/tonal images. It is a painting later on in the book, of a land-dwelling boy, Howie, looking for the seamaiden he has befriended in her pool; instead he is greeted by the horrifying Jenny Greenteeth. In this image I have reversed the silhouette, so that while he is clearly defined, black silhouette, Jenny Greenteeth is horribly pale and ghostly and her pool is dark and shadowy. I wanted that image to feel like a shock.

What’s it been like working with each other? Can you talk about your creative process?

Berlie: It has been a wonderful, creative experience. As well as being an extremely talented colourist, Tamsin is highly creative and quick-thinking. We would talk about an image, for example, what our sea-maiden would look like, how about angel fish, with their long floating tendrils, and within a few days Tamsin would produce these incredibly elegant and utterly lovely flowing images.

Tamsin: Berlie is a very visual writer, her storytelling is full of colour, atmosphere and descriptions. I feel like she did most of the work for me! We talked a lot throughout the creation of this book; I’d often check with Berlie what time of day she imagined a scene happening so I could get the light right, for example. However, there is a very important, third person who needs to be mentioned, and that is Becky Chilcott, our wonderful designer. It was Becky who first suggested that I should work in pure silhouette with my bold colour behind it. It is a very classical and a universal language of the telling of folklore, mythology and fairy tales. Although most people today think of Jan Pieńkowski or Arthur Rackham’s silhouette work, it is actually a visual language that we can trace back to antiquity – think of all those silhouette sirens and warriors painted around ancient Greek vases, or the neolithic art in caves that uses the shapes of animals and spirit humans acting out scenes. I love working with Berlie because we get to discuss all this fascinating stuff: the folklore, the way you might paint music, the importance of atmosphere, and the way that mythological creatures might look.

Can you think of a song and a film that might link to The Seamaiden’s Odyssey?

Berlie: Some time ago I wrote a selkie story called Daughter of the Sea, which was inspired by a folk-song called the Selkie of Skule Skerry. I’ve known and loved that song nearly all my life, and it stayed with me during the writing of this very different story. That book eventually became a children’s opera, with beautiful music by Richard Chew. That, too, haunted me while I was writing The Seamaiden’s Odyssey.

Tamsin: I know that Selkies are different sort of ocean creatures, but there is a wonderful song by folk musician Emily Portman, called Greystone, which is the song of a young selkie maiden, singing to her mother as she explores the world alone. Emily is an amazing musician and a folklorist, and she’s woven into her song a fragment of Hebridean music written down generations ago, after it was said to have been heard sung by the selkie folk themselves. To me that song seems somehow connected to our book. It is very haunting and strange, and utterly beautiful.

Finally, can you describe The Seamaiden’s Odyssey in three words?

Berlie: What I hoped to achieve was something ageless, thought-provoking, and lyrical.

Tamsin: If I had to sum up my illustration approach in this in three words, I’d choose: movement, contrast and colour.