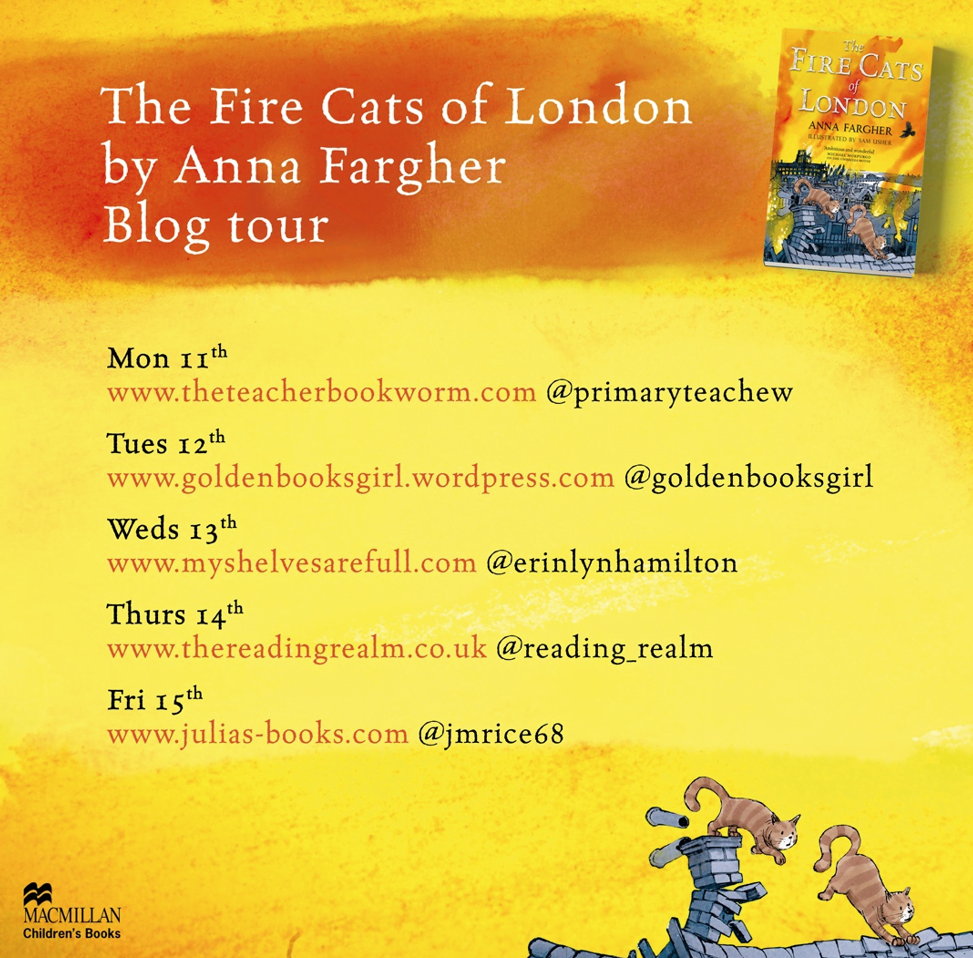

To mark stop 4 of #TheFireCatsofLondon blog tour, I’m delighted to welcome Anna Fargher into The Reading Realm to reveal some little known facts about The Great Fire of London.

Anna’s latest book, The Fire Cats of London, takes the reader to historic London at the time of the Great fire in a story of daring, courage and loyalty. Featuring two young wildcats, Asta and Ash as they journey through London determined to return home, it’s ideal for 8 to 12 readers who are fans of anthropomorphic stories.

Anna Fargher on The Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London is the most infamous fire in British history. Studied in schools from KS1, you’re probably aware of the devastation it caused to many beautiful buildings and how it changed the city of London forever. However, there’s a lot of misinformation out there. Read on for Six things you might not know about the Great Fire of London

It didn’t start on Pudding Lane

Thomas Farriner’s bakery was actually located just off of Pudding Lane in Fish Yard, which is now today’s Monument Street.

The blaze lasted months not days

Samuel Pepys recorded that cellars were still burning in March 1667.

It didn’t stop the Great Plague

Deaths from the pestilence had already started to ebb, and new infections were declining by September 1666.

More than six people were killed in the disaster

Famously, only six people are recorded as dying in the fire. The truth is that most of those who died were poor, working, or lower-middle-class making it almost impossible to know how many people actually died.

There was a real plot to burn the City of London

In April 1666, a group of parliamentarians led by John Rathbone and William Saunders were found guilty of trying to assassinate Charles II and setting fire to the city. Their “Hellish design” was planned to take place on the anniversary of Oliver Cromwell’s death, 3 September – a day after the start of the actual Great Fire of London.

The Great Fire of London was predicted

Two comets appeared in 1664 and 1665 and were interpreted as harbingers of The Great Plague and The Great Fire respectively. People were also nervous that the biblical number 666 in 1666 indicated evil was brewing. Samuel Pepys wrote: ‘For the whole year, the population of London had a great sense of foreboding, because the year had the number of the devil in it – 666.’

As early as the 15th century, Nostradamus and Mother Shipton both recorded visions predicting The Great Fire. In 1651, an astrologer named William Lilly printed a prophecy entitled Monarchy or No Monarchy that contained cryptic illustrations of the future of England, including a city being devoured by flames. Lilly was suspected of plotting The Great Fire.