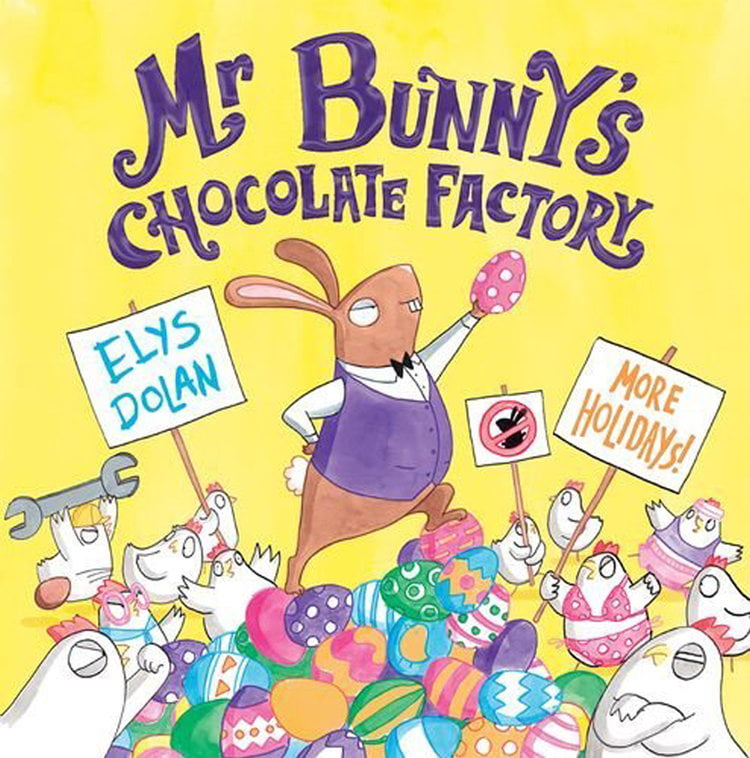

This seems like the perfect time to sit down with Elys Dolan, children’s author and illustrator, whose books include Mr Bunny’s Chocolate Factory, The Clockwork Dragon and Steven Seagull: Action Hero!

How is Mr Bunny’s Chocolate Factory similar to your other books? How is it different?

Mr Bunny is similar to some of my other books in the way that it’s very detailed. There’s lots of things going on, lots of subplots and lots of conversations. I like to make books that you can read again and again and still find something new. It’s a bit different in that in amongst the funny it has a solid message about fairness. This isn’t something I set out to make a book about. It evolved naturally as I got to know the chickens and their predicament.

What are the main themes you would like readers to take from Mr Bunny’s Chocolate Factory?

Again it’s that theme of fairness but also knowing that if you don’t think something’s fair you can question it and stand up to authority, even if you’re a chicken or a quality control unicorn. Also, I want the reader to have a jolly good laugh while all that’s going on.

How difficult is it writing something that aims to make children laugh and think? How do you balance the two?

I don’t think that I do often consciously try to balance those two aspects. I find what exactly a book is going to be about is dictated by the characters and the world they inhabit. The more I get to know them through drawing then the more their thoughts, feelings, quirks and motivations become clear. For me, once I start to shape all this into an interesting and engaging story the balance between what’ll make a reader think and what’ll make them laugh finds a natural equilibrium.

You won at the Lollies in 2018! Why do you think awards like the Lollies are so important?

Because they shine a light on funny books, which are so often overlooked and undervalued. For instance, the results of the Lollie’s wasn’t reported in any national newspapers despite other book awards receiving coverage. I think there’s still a perception that all children’s literature must be moralistic and improving in an earnest manner. But, as Terry Pratchett said, funny is not the opposite of serious. Also children do want funny books. In the most recent Scholastic Kids & Family Reading Report the children surveyed said the thing that they wanted most in a book is that it should make them laugh. If we’re going to foster a lifelong love of reading in children then we need to give them books that they really want to read.

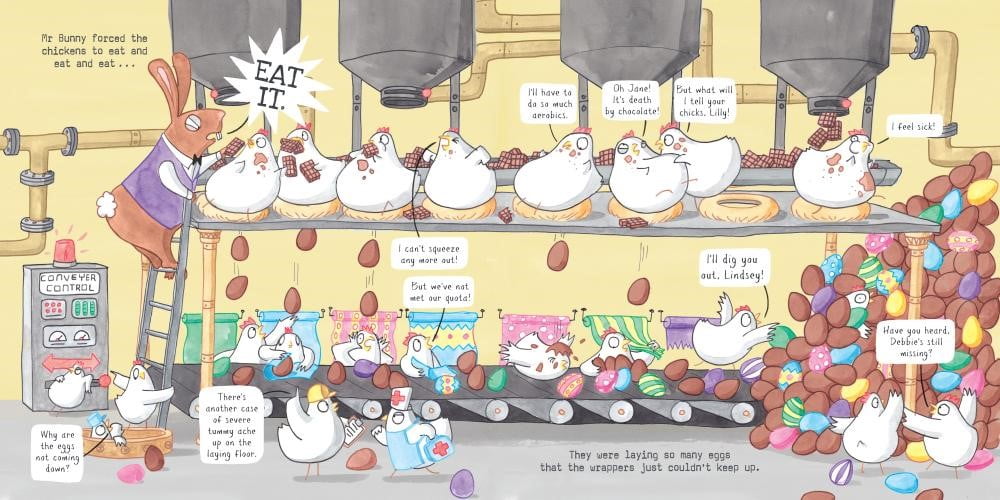

I love this double page spread from Mr Bunny’s Chocolate Factory! Can you tell us a little bit more about your choice of layout, colour, design and what you were trying to achieve?

In this spread I wanted to keep those light and fun Easter colours but contrast it with the way things are going downhill for the chickens, showing the gradual decline of Mr Bunny’s factory. It’s a busy spread with lots of characters because I intended to show plenty of instances of the chickens trying to cope with the situation; the way in which they manage feeling sick and the need to do aerobics with Mr Bunny’s demands for more eggs. Along with that the many details and actions contribute to the feel of mounting chaos I was wanted this spread to have.

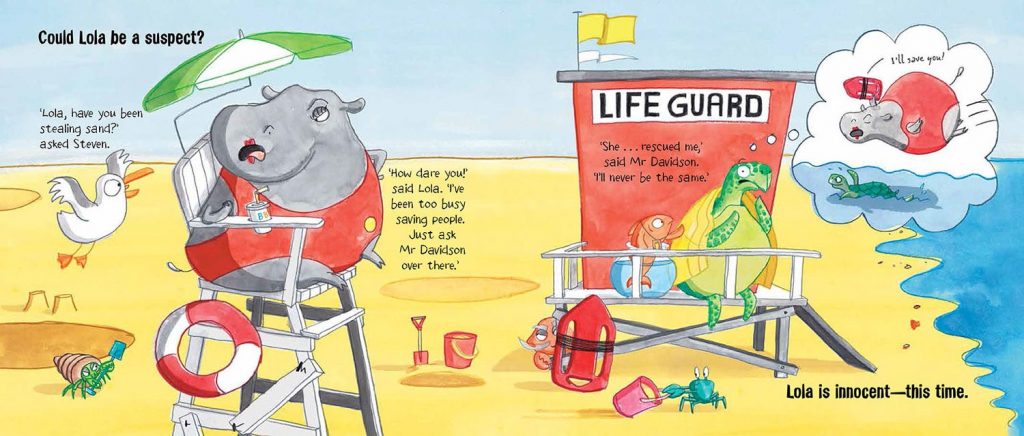

This page in Steven Seagull: Action Hero really made me giggle! There’s a very clever interplay between the words and pictures going on. I also love the characters’ facial expressions and body language (poor Mr. Davidson!). Can you talk a little bit more about how you develop your stories and humour through the characters’ body language and facial expressions?

When I’m coming up with character based humour I’m always trying to make them do things that make me laugh. Before I start illustrating a book and roughing out how each page will look, I fill sketchbooks with pages of character drawings of them doing everything I can possibly imagine so that I know that character really well. While I’m doing that I subconsciously start drawing them doing things to make me laugh to keep myself entertained, so the way I exaggerate them or the expression I choose is instinctive. If I sit down and say to myself ‘okay, now I’m going to draw some really funny characters’ they’re inevitably not that funny because the humour has become contrived. I have to let it happen naturally.

I know you’re a lecturer on the MA in Children’s Book Illustration at the Cambridge School of Art. What do you particularly enjoy about this role? Do you think teaching in this capacity has helped your own writing and creative process?

I love being surrounded by people who are just as nerdily excited by children’s books as I am. Being an author and illustrator can be quite an isolating job. You spend a lot of your time in a room on your own colouring in for hours on end. So it’s great to go out and talk to actual humans. Also, being able to hear all my students exciting ideas and sit down and refine those ideas and problem solve really keeps me on my toes. I think being a teacher makes me a better illustrator and being a practicing illustrator makes me a better teacher so the roles connect well.

What advice would you give to young children who would like to pursue a career in illustration and writing?

If you want to be an illustrator, always be drawing. Keep a sketchbook in your bag and draw what you see in the real world along with drawing from imagination. Observational drawing doesn’t just help you refine your skills as a draftsman but it lets you absorb the world around you, and so making you a more interesting person and your work more interesting. You’ve never really seen something properly until you’ve drawn it.