“Reading helps you to develop an explorer’s heart, and the world never looks quite the same once you’ve glimpsed it through someone else’s eyes…”

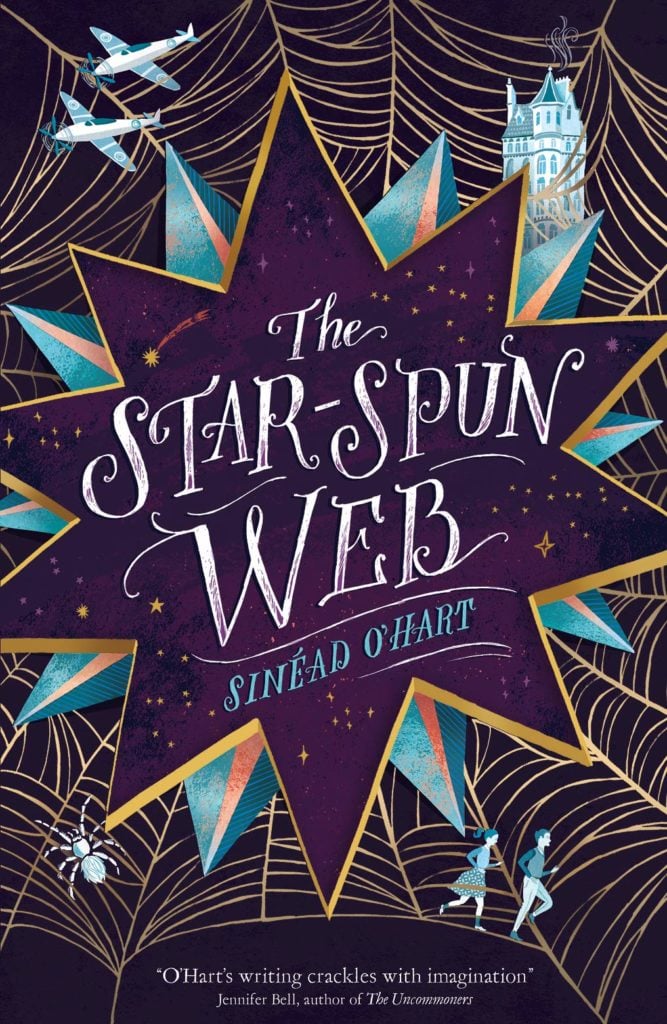

I’m delighted to invite Sinead O’Hart into The Reading Realm to talk about her magical, thrilling, moving new story ‘The Star-Spun Web’…

About the book

Without giving too much away, can you tell us a bit about your new book ‘The Star-Spun Web’’?

The Star-Spun Web is the story of Tess de Sousa, who has grown up in the loving confines of Ackerbee’s Home for Lost and Foundlings in a city called Hurdleford. She is protected and deeply cared for, and surrounded by friends, but she knows nothing about her early life or origins. So, one day, when a mysterious stranger shows up claiming to be a distant relative, nobody is more surprised than Tess – besides perhaps Miss Ackerbee, the woman who has guarded Tess since the day she was born. Miss Ackerbee knows something secret about Tess, something so secret even Tess herself doesn’t know it, and it’s something which means she couldn’t possibly have a relative. Not in this reality, at least… Instead of running from the stranger, Tess decides to go with him in order to try to uncover the truth about herself and her parents, taking with her a strange object which Miss Ackerbee says was left with her the day she appeared on the doorstep of the Home, an object which has a huge and world-changing power. As Tess works to figure out what the object is for, and who she is, she soon discovers that the stranger, Mr Cleat, is one step ahead of her all the time. Can she get to the bottom of her strange and frightening talents before Mr Cleat uses her to accomplish something terrifying?

What would you say the main themes in your stories are?

I think I tend to write stories about fiercely independent children, and I love creating girl characters who go ‘against type’; girls who love science, for instance, or who like to think logically, or who relish getting stuck into the action, or all of the above! I also love to explore the emotional side of my boy characters, which doesn’t in any way stop them from being ‘heroes’ – they’re every bit as brave and accomplished and clever as the girls. I love stories which rely on cooperation and interdependence between the child characters – nobody ‘rescues’ anyone else, but everyone has a role in bringing things to their conclusion. I also think family is a theme: both my books so far have had families, in all their weird and wonderful permutations, at their heart, and also the power and importance of loyal friendships.

‘The Eye of the North’ was extremely popular. How is ‘The Star-Spun Web’’ similar? How is it different?

Well, thank you for saying so! I’m glad The Eye of the North was enjoyed by so many readers. The Star-Spun Web has a few similarities, insofar as it features a strong, science-loving girl and an emotionally complex and very brave boy at its heart, and they’re both about finding the truth behind your family and yourself. Besides that, they’re very different! The Eye of the North features vast amounts of travel, utilising a variety of weird and wonderful conveyances like airships and amphibious boats, and an array of mythical creatures; The Star-Spun Web technically takes place all in one city, and isn’t reliant on mythology and folklore in the same way. There are more child characters in Web, which I love, and I really enjoyed writing their interactions and exploring their friendships.

As I was reading, I was reminded of Philip Pullman’s ‘His Dark Materials’ trilogy. What was your inspiration for this story? Are there any books that particularly inspired you?

I don’t think there’s a greater compliment that can be paid to any writer than to have His Dark Materials mentioned in the same breath as their work! Of course, those amazing books are a huge influence on me, as they are on everyone. I read a lot (besides writing, it’s my favourite thing to do) and I think everything I read influences me, but I don’t think any books in particular lie behind The Star-Spun Web. Every book I read teaches me something, whether it’s how to craft characters or how to make dialogue sing off the page, or the heights I’d love to see my own work reaching. Books I’ve loved recently, and which I read during the writing of The Star-Spun Web, include Vashti Hardy’s Brightstorm, Juliette Forrest’s Twister, Sarah Driver’s The Huntress: Storm, Peter Bunzl’s Skycircus, and Abi Elphinstone’s SkySong. All these books are wonderful, and I hope some small fragments of their brilliance have crept into my own writing.

There are lots of references throughout the book to quite complex scientific ideas, most notably the theory of alternate worlds. What research did you conduct into this? Is this an area that you’ve always been interested in?

My own background is firmly in the arts and humanities – I have a PhD in medieval English literature – and I have no training in science whatsoever, besides what I learned at school. Having said that, I love science, and have always been fascinated with the concepts behind certain scientific principles. From childhood I would sit, absorbed, in books about space and time, interstellar travel, and alternate realities. One of my favourite books as a child was Madeleine l’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, which has been a huge influence on my life and thinking. I’m very bad at maths, sadly, which means studying things like physics has always been a bit beyond my abilities, but as a layperson I love to think about the ideas and allow my imagination to go wild. I revisited favourite books such as Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time while thinking about The Star-Spun Web, and did some internet-based research into the life of Erwin Schrodinger, whose ideas about the many-worlds theory were an influence on my own book.

I love the idea of the children having Moose and Violet as their sidekicks! They are wonderful, intelligent, comforting companions. Why did you decide to have a mouse and a tarantula accompany the children on their adventures, as opposed to, say, a dog, cat or bird? How do you think the story would be different if Moose and Violet could talk?

Thank you! I think Moose and Violet might just be my favourite characters. I have no real idea why Violet is a tarantula – she just turned up in my head that way, and I didn’t see any reason why she should change.

I loved the idea of an animal which might be seen as frightening or off-putting becoming the sidekick of a girl like Tess, and I also think scary animals get a raw deal in fiction so I wanted to do my bit to address that. I love M.G. Leonard’s approach to beetles in her Beetle Boy trilogy, and she was a definite inspiration! Giving Tess a kitten or a bird might have been a bit predictable and boring, but life is never boring with a tarantula around. As to why Moose is a mouse: I suppose because he’s small, portable and easy to care for, a bit like Violet! I chose not to have the animal characters talk as I wanted them to be as ‘correct’ as possible.

In a much earlier draft, Violet had what might be called extra-special abilities; she could understand human speech, and she was able to dance. These were charming things, but in the final version I made her as realistic as possible, and I did the same for Moose. I think if they could talk, the book would be a bit more whimsical, which wasn’t the feeling I was going for. I also think that Tess and Thomas are both quite solitary figures; even though Tess grows up with lots of other children she always feels like something is missing, and of course Thomas is completely alone, besides his awful ‘guardian’. Having a confidant who simply listens, as opposed to being able to talk back, seemed to suit their characters.

If you could have your own Violet or Moose, which animal would you choose and what might they be called?

I think I’d like a wild animal with whom I had a particular connection and which was linked to me in some way, but which had its own freedom and its own life and lived on its own terms. I love the relationship between Abi Elphinstone’s character Moll and the wildcat Gryff in her Dreamsnatcher trilogy; Moll doesn’t own Gryff, and he’s his own creature. I love to see animals in the wild, and so something like a wild bird which I could admire from a distance would be perfect. I’d also love to call them something based in Irish – so perhaps Radharc (pronounced RYE-irk) would suit. It means ‘vision/sight’ or ‘view’.

What struck me particularly throughout the story, is the sheer independence and bravery of the children – they certainly do not need adults to save them! Their decisions drive the story forward and provide many of the twists and surprises. Could you talk about this a bit more?

Thanks! This is something really important to me. I love writing, and reading about, child characters who drive the action through their own bravery and intelligence. There’s something frustrating about a plot which relies on the interference of adults to bring it to its conclusion (though of course getting a little bit of help is all right). I liked creating adults in The Star-Spun Web who respected and trusted the child characters; Miss Ackerbee and Rebecca, the house-mistresses in the Home where Tess grew up, have faith in the abilities of their girls and give them the freedom they need to save the day, and it was important to me that it was the girls themselves who found a way to help one another. I think it makes for a more interesting story, as well as a more thrilling one, if the action and momentum centre on the children – after all, the book is about them, and the people it’s written for are children too, so what’s the point in over-involving the meddling adults? They just make a mess of everything.

Your writing process

What does a day in the life of Sinead O’Hart look like when you’re writing?

My days start early, as I have a three-year-old! On days when my daughter is in preschool, I start work as soon as I’m home from dropping her off. I usually have about two hours most mornings to devote to writing, or life-admin, or whatever needs doing. After that all the work I do takes place after my little one is in bed, which means it can be a struggle. I try to work at weekends too, and my husband does his best to help out when I’m nearing a deadline, but to be honest my writing days look a lot like my non-writing days: barely-managed chaos!

There are multi-storylines throughout the book that all cleverly weave together and build to a thrilling conclusion. How did you plan and manage all the different storylines?

My plots usually come to me all in one piece, so to speak – I tend to plan and manage them all together, as a unit, and it’s only in the writing that they become nuanced and distinct.

In this book, the story didn’t really come together properly until I started writing sections from Thomas’s point of view, too; as soon as I did that, the threads of his plot really began to come to the fore and the book was much more satisfying as a result. As with The Eye of the North, I wanted to write a story where the main plotline was complemented by the sub-plot, and one which brought both plotlines to a satisfying and mutually dependent conclusion – and I hope I managed it.

Do you have a favourite part of the writing process? Do you have a least favourite part?

I think I like all of it, but my favourite bit is probably the feeling you get when you’re on a roll – when you’re writing so freely that the words are flowing and you’re right there in the world you’re creating. These moments don’t happen every time you sit down to write, and so I treasure them when they come. I dislike days when writing feels like chipping away at a granite wall – usually, that’s a sign I need to stop. On days like that, my brain is telling me to take a rest and do something else, or that my plotting is going down the wrong road. I’ve learned, the hard way, to heed the warning.

What did you edit out of this book? Why?

This book was essentially written three times, as each draft was so different. The first two drafts were both told exclusively from Tess’s side, like the narrator was sitting on her shoulder; Thomas was there too, of course, but we only saw him through Tess’s eyes. The breakthrough came on the third draft, when my editor gently reminded me that the best part of The Eye of the North came when I broke the chapters between my characters’ points of view. As soon as I started the third draft, and brought the reader right into Thomas’s world, the book came alive. So, I suppose I edited out a lot of unnecessary filler detail from Tess’s side of things, and it was all for the best. Always listen to your editor!

You mention in your ‘Author Acknowledgements’ the success of ‘The Eye of the North’ and the role social media and Twitter played in this. How do you feel social media has changed children’s publishing?

I don’t know if I’m best placed to comment on how children’s publishing has been changed by social media as I’m a newcomer to the field, relatively speaking. I’m old enough to have had several careers under my belt before social media came on the scene, but my career in writing has coincided with the upswing in social media. So, to me, the two have always been hand in hand. I think Twitter, for me, is a brilliant place where I get to meet and interact with writers, editors and agents I admire, and it’s been massively helpful to me in building networks and getting to know people. It’s important to have a ‘family’ in this industry, people who’ll support you and help you when things get hard. I like to show support to others, and it’s a wonderful comfort to get it back in spades when I need it.

I feel like there’s so much more to explore with Tess and Thomas – will there be a sequel to ‘The Star-Spun Web’? what do you envisage might happen next?

It would be nice to visit them again, wouldn’t it? I think Thomas and Tess have many more worlds to explore, and the truth about their parents is still out there. I don’t have firm plans for a sequel – these things are usually out of authors’ hands! – but I think there are lots more stories to tell with these two.

Teaching and education

As a teacher, I’m always interested in an author’s point of view about inspiring a love of reading and writing in our children…

What are your earliest memories of reading and writing?

I owe my career as a writer to two books: Alan Garner’s Elidor and Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince. The first ‘book’ I ever wrote was a sequel to The Little Prince, when I was about seven, and my world was changed forever when I read Elidor, aged eight. It made me want to be a writer, even if it took me years to believe I could do it. My parents told me I was an early reader and that I liked to tell myself stories (usually with my own illustrations!) from when I was very little – so I guess this career was inevitable, really!

Tess is drawn to ‘The Secret Garden’ but doesn’t really enjoy the story. Did you have a favourite story when you were younger? What advice would you give to children who say they don’t enjoy reading?

I actually like The Secret Garden, though I haven’t read it for many years. I’m not sure why I chose it as Tess’s bugbear in The Star-Spun Web!

I couldn’t tell you what my favourite story was as a child, as I had so many. Certainly Elidor, The Little Prince, The Phantom Tollbooth, A Wrinkle in Time, and The Hounds of the Morrigan stand tall in my memory, but I also loved stories and folktales like ‘The Magic Porridge Pot’ and ‘The Enormous Turnip’, which I enjoy sharing with my own little girl now, using the same books my parents read to me when I was small. As for advice to children who don’t like reading: I firmly believe that reading is something everyone can enjoy, but there are loads of ways to read. You don’t have to read just books, at least not all the time.

Graphic novels are great and they help to develop ways of reading which go beyond words printed on a page – learning to read through imagery is a brilliant skill. Books written in free verse are great and can appeal to kids who enjoy music, as the words can often be put to a beat or sung; they’re also fast reads, usually, though very rewarding. Non-fiction books are fantastic – I loved reading dictionaries and books of facts as a kid – and they’re just as absorbing and vital as fiction books. Magazines about things which interest you are fantastic, and there are loads available if you look – from music to football to farming to car-racing – and getting stuck into one of them definitely counts as reading. Audio books can help if children struggle with print, or they don’t like to sit down with a printed book. I always feel children should be allowed to read whatever they like, for as long or as short a time as they like, and that reading should be modelled by teachers and parents as an enjoyable thing to do.

I read anything and everything as a kid; my parents trusted me to judge for myself whether something was suitable or not. If I read a book which was too ‘grown-up’, I simply let it slide over me or I put the book away until I was ready for it. Children are remarkable like that! If you’re a child who isn’t interested in reading, or you find yourself bored with the books you’ve been picking up, I’d advise asking a bookseller, librarian or teacher for help with recommendations for books which mirror your interests, or try reading in a format you’re not familiar with – a graphic novel or an audio book, maybe. And keep going until you find the story for you.

What advice would you give to teachers about how to develop reading for pleasure in their classrooms and schools?

Let children see that you’re an adult who enjoys reading, and be enthusiastic about it as often as possible. Read in public, unashamedly, and let it be known you’re always up for a bookish chat!

As well as that, I’ve seen many teachers doing things like a ‘Reading World Cup’ in their classroom, and a recent brilliant idea I saw on Twitter was to make a display called ‘Bookflix’ which mimics Netflix, showing newly released books and recommended reads. I also try to support teachers’ calls for posters and letters for their classroom reading displays as often as possible, as I think they’re brilliant ways to bring books into your students’ lives. Getting in touch with authors on Twitter and printing out their responses for a display is easy to do, and effective. I know I would have loved that, had it existed when I was at school. I think it helps if teachers try to keep up to date with what’s being published so that they can make recommendations to their pupils, though I know this can be quite a drain on resources as so many amazing books are being published at the moment.

How would you envisage teachers using your book in their classrooms? Do any activities or ideas spring to mind?

I think The Star-Spun Web could be used to look at life during the Second World War, and perhaps the contrast between Britain and officially neutral Ireland. It’s amazing how many fantastic books have been written lately which take World War I or World War II as a theme, and my book could be contrasted with any of them. I think it could also be used to think about alternate realities – pupils could make up their own theories about how it all works and develop their own systems of getting from one world to another. I’d also love to see research projects being done into local history – The Star-Spun Web takes a Dublin tragedy as a central plot point, one which might be unfamiliar to lots of readers. We all know about things like the Blitz, but perhaps your area has its own war story, one which mightn’t appear in history books but which is important to your family or your town.

Children are always fascinated by authors and seem to always want to know where they get their ideas from. So, on behalf of all the children I’ve ever taught, where do you get your ideas and inspiration from?!

I always tell children who ask this question that I follow my ABC – Always Be Curious! Keep your feelers out all the time to examine the world around you.

Look for interesting sights and sounds; listen to conversation snippets as you go about your life (without being rude, of course!); ask yourself questions about strange or interesting things you see or hear, and notice as much as you can. Absorb as much as possible. I get inspired by misspelled signs, newspaper headlines, interesting and juicy words I’ve never heard before, funny or unusual people I might see on the street or chunks of conversation I might overhear, paintings and pictures and music and all forms of art – and, of course, other books. Keep a notebook for your ideas, whether they’re flashes of dialogue, character names, settings, or simply ‘What if?’ scenarios, and you never know: one day, some of them might come together in a new and fascinating way, and a story will start to grow.

What advice would you give to any budding young authors?

As well as becoming a sponge and soaking in the world around you, the most important thing to do is read (or take in stories) as much as you can. Every story you read, or every graphic novel you enjoy, or every movie you watch, teaches you something about stories and how they’re constructed – usually, you don’t even notice you’re learning. Keep an ideas notebook and never let an idea escape, as they’re tricksy, slippery little things. Doodle, sketch, and draw cartoons as well as noting things down with words if that’s easier for you. When you start to write, don’t place any limits on yourself and enjoy telling yourself a story. Write what you love. Then, it always helps to put something aside for a few weeks once you’ve finished it before coming back to it – usually, you’ll spot things you can improve on or fix. And the most important thing? Have fun. Enjoy expressing yourself, and the sheer magic of creating something from your head that didn’t exist before you thought of it. Take pride in your work and as long as it’s making you happy, never give up.

Mr. Cleat tells Tess that every scientist needs ‘attention to detail, methodical thinking and seemingly endless patience’. What do you think every reader needs?

I think all you need to be a reader is to be open to adventure, and to be willing to let yourself slip away into the world of a story. Reading helps you to develop an explorer’s heart, and the world never looks quite the same once you’ve glimpsed it through someone else’s eyes.

It’s an amazing power, to be able to inhabit the mind and body of another person – perhaps an alien lifeform, perhaps an animal, perhaps a boy or girl nothing like yourself – and sometimes reading takes courage, too. It changes you, giving you empathy and compassion and understanding of other people and faraway places. So, if you’re ready to experience something completely new, the best way to do it is through reading a book.

Apart from your own book, is there another book or author you would recommend to children that you’ve enjoyed recently?

I love recommending books. Recently, I have loved Brightstorm by Vashti Hardy, Twister by Juliette Forrest, TIN by Pádraig Kenny, The Way Past Winter by Kiran Millwood Hargrave, Sky Song by Abi Elphinstone, Begone the Raggedy Witches by Celine Kiernan, Death in the Spotlight by Robin Stevens, and The Skylarks’ War by Hilary McKay. I could go on forever…

Finally, can you describe your new book ‘The Star-Spun Web’ in three words? Mysterious, science-tinged, thrilling.

Sinead has very kindly put together a list of interesting, educational places you could visit to support your understanding of the book and develop a love of science! Click the link below to download!

Fantastic Science in the real world places to visit

THE STAR-SPUN WEB

Written by Sinéad O’Hart

Published 7th February 2019

RRP £6.99

ISBN 9781788950220

Format Paperback

Publisher Stripes Publishing (An imprint of the Little Tiger Group)

Age 8-12 years